Children’s recognition of working donkeys’ needs in Tuliman, Mexico: Preliminary observations

Main Article Content

Abstract

Veterinaria México OA

ISSN: 2448-6760

Cite this as:

- Tadich Gallo TA, de Aluja A, Cagigas R, Galindo F. Children’s recognition of working donkeys’ needs in Tuliman, Mexico: Preliminary observations. Veterinaria México OA. 2016;3(4). doi: 10.21753/vmoa.3.4.404

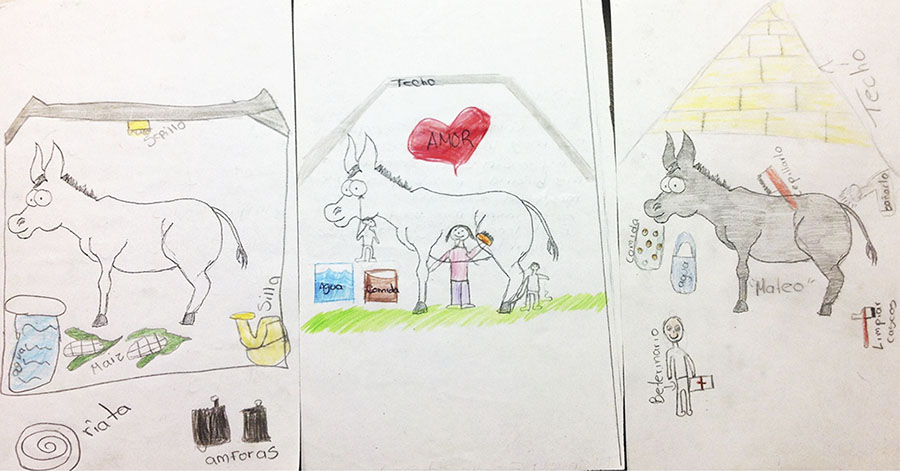

Figure 2. Examples of children’s drawings including the needs they identified. Some of the needs drawn include corn (food), water, grooming and love, as represented by a heart (positive human-animal bond).

Article Details

References

Tadich T, Stuardo L. Strategies for improving the welfare of working equids in the Americas: a Chilean example. Rev Sci Tech Off Int Epiz. 2014; 33:203-211.

Tadich T, Escobar A, Pearson RA. Husbandry and welfare aspects of urban draught horses in the south of Chile. Arch Med Vet. 2008; 40:267-273.

Farm Animal Welfare Council. Second report on priorities for research and development in farm animal welfare. Farm Animal Welfare Council, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. London; 1993.

Broom DM. Needs, freedoms and the assessment of welfare. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1988; 19:384-386. doi: 10.1016/0168-1591(88)90023-8.

Mellor DJ. Moving beyond the “five freedoms” by updating the “five provisions” and introducing aligned “animal welfare aims”. Animals. 2016; 6, Nº 59-1. doi: 10.3390/ani6100059.

Myers OE, Saunders CD, Garrett E. What do children think animals need? Aesthetic and psycho-social conceptions. Environ Educ Res. 2003; 9:305-325. doi: 10.1080/13504620303461.

Noddings N. Caring. Berkeley, University of California Press. 1984.

de Aluja A. The welfare of working equids in México. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1998; 59:19-29. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(98)00117-8.

Pritchard JC, Lindberg AC, Main DCJ, Whay HR. Assessment of the welfare of working horses, mules and donkeys, using health and behavior parameters. Prev Vet Med. 2005; 69:265-283. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2005.02.002.

Wilson RT. Specific welfare problems associated with working horses. Chapter 9. In: Waran N, editor. The welfare of horses. Kluwer Academic Publisher, Springer. The Netherlands. Pp 203-218. 2007.

Fraser D, Weary DM, Pajor EA, Milligan BN. Scientific conception of animal welfare that reflects ethical concerns. Anim Welf. 1997; 6:187-205.

Damerell P, Howe C, Milner-Gulland EJ. Child-orientated environmental education influences adult knowledge and household behavior. Environ Res Lett. 2013; 8:015016. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/8/1/015016.

Fidler M, Coleman P, Roberts A. Empathic response to animal suffering: societal versus family influence. Anthrozoos. 2000; 13:48-51.

McPhedran S. A review of the evidence for associations between empathy, violence, and animal cruelty. Aggress Violent Beh. 2009; 14:1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.07.005.

Kellert SR. Attitudes towards animals: age related development among children. In: MW Fox and LD Mickley, editors. Advances in animal welfare science. Washington DC: The Humane Society of the United States; 1984. p. 43-60.

Calderón-Amor J, Luna D, Tadich T. Study of the levels of human-human and human-animal empathy of Veterinary Medicine students from Chile. J Vet Med Educ. Accepted. doi: 10.3138/jvme.0216-038R.

License

Veterinaria México OA by Facultad de Medicina Veterinaria y Zootecnia - Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence.

Based on a work at http://www.revistas.unam.mx

- All articles in Veterinaria México OA re published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC-BY 4.0). With this license, authors retain copyright but allow any user to share, copy, distribute, transmit, adapt and make commercial use of the work, without needing to provide additional permission as long as appropriate attribution is made to the original author or source.

- By using this license, all Veterinaria México OAarticles meet or exceed all funder and institutional requirements for being considered Open Access.

- Authors cannot use copyrighted material within their article unless that material has also been made available under a similarly liberal license.